Meditation

Meditation is a practice where an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state.[1]:228–29[2]:180[3]:415[4]:107[5][6] Scholars have found meditation difficult to define, as practices vary both between traditions and within them.

Meditation has been practiced since antiquity in numerous religious traditions, often as part of the path towards enlightenment and self realization. The earliest records of meditation (Dhyana), come from the Hindu traditions of Vedantism. Since the 19th century, Asian meditative techniques have spread to other cultures where they have also found application in non-spiritual contexts, such as business and health.

Meditation may be used with the aim of reducing stress, anxiety, depression, and pain, and increasing peace, perception,[7] self-concept, and well-being.[8][9][10][11] Meditation is under research to define its possible health (psychological, neurological, and cardiovascular) and other effects.

Etymology

The English meditation is derived from Old French meditacioun, in turn from Latin meditatio from a verb meditari, meaning "to think, contemplate, devise, ponder".[12][13] The use of the term meditatio as part of a formal, stepwise process of meditation goes back to the 12th century monk Guigo II.[13][14]

Apart from its historical usage, the term meditation was introduced as a translation for Eastern spiritual practices, referred to as dhyāna in Hinduism and Buddhism and which comes from the Sanskrit root dhyai, meaning to contemplate or meditate.[15][16] The term "meditation" in English may also refer to practices from Islamic Sufism,[17] or other traditions such as Jewish Kabbalah and Christian Hesychasm.[4]

Definitions

Meditation has proven difficult to define as it covers a wide range of dissimilar practices in different traditions. In popular usage, the word "meditation" and the phrase "meditative practice" are often used imprecisely to designate practices found across many cultures.[4][18] These can include almost anything that is claimed to train the attention of mind or to teach calm or compassion.[19] There remains no definition of necessary and sufficient criteria for meditation that has achieved universal or widespread acceptance within the modern scientific community. In 1971, Claudio Naranjo noted that "The word 'meditation' has been used to designate a variety of practices that differ enough from one another so that we may find trouble in defining what meditation is."[20]:6 A 2009 study noted a "persistent lack of consensus in the literature" and a "seeming intractability of defining meditation".[21]:135

Dictionary definitions

Dictionaries give both the original Latin meaning of "think[ing] deeply about (something)";[6] as well as the popular usage of " focusing one's mind for a period of time",[6] "the act of giving your attention to only one thing, either as a religious activity or as a way of becoming calm and relaxed",[22] and "to engage in mental exercise (such as concentrating on one's breathing or repetition of a mantra) for the purpose of reaching a heightened level of spiritual awareness."[5]

Scholarly definitions

In modern psychological research, meditation has been defined and characterized in a variety of ways. Many of these emphasize the role of attention[4][1][2][3] and characterize the practice of meditation as attempts to get beyond the reflexive, "discursive thinking"[note 1] or "logic"[note 2] mind[note 3] to achieve a deeper, more devout, or more relaxed state.

Bond et al. (2009) identified criteria for defining a practice as meditation "for use in a comprehensive systematic review of the therapeutic use of meditation", using "a 5-round Delphi study with a panel of 7 experts in meditation research" who were also trained in diverse but empirically highly studied (Eastern-derived or clinical) forms of meditation[note 4]:

Several other definitions of meditation have been used by influential modern reviews of research on meditation across multiple traditions:[note 7]

- Walsh & Shapiro (2006): "[M]editation refers to a family of self-regulation practices that focus on training attention and awareness in order to bring mental processes under greater voluntary control and thereby foster general mental well-being and development and/or specific capacities such as calm, clarity, and concentration"[1]:228–29

- Cahn & Polich (2006): "[M]editation is used to describe practices that self-regulate the body and mind, thereby affecting mental events by engaging a specific attentional set.... regulation of attention is the central commonality across the many divergent methods"[2]:180

- Jevning et al. (1992): "We define meditation... as a stylized mental technique... repetitively practiced for the purpose of attaining a subjective experience that is frequently described as very restful, silent, and of heightened alertness, often characterized as blissful"[3]:415

- Goleman (1988): "the need for the meditator to retrain his attention, whether through concentration or mindfulness, is the single invariant ingredient in... every meditation system"[4]:107

Separation of technique from tradition

Some of the difficulty in precisely defining meditation has been in recognizing the particularities of the many various traditions;[25] and theories and practice can differ within a tradition.[26] Taylor noted that even within a faith such as "Hindu" or "Buddhist", schools and individual teachers may teach distinct types of meditation.[27]:2 Ornstein noted that "Most techniques of meditation do not exist as solitary practices but are only artificially separable from an entire system of practice and belief."[28]:143 For instance, while monks meditate as part of their everyday lives, they also engage the codified rules and live together in monasteries in specific cultural settings that go along with their meditative practices.

Forms and techniques

Classifications

In the West, meditation techniques have sometimes been thought of in two broad categories: focused (or concentrative) meditation and open monitoring (or mindfulness) meditation.[29]

Focused methods include paying attention to the breath, to an idea or feeling (such as mettā (loving-kindness)), to a kōan, or to a mantra (such as in transcendental meditation), and single point meditation.[30][31]

Practices using both methods[33][34][35] include vipassana (which uses anapanasati as a preparation), and samatha (calm-abiding).[36][37]

In "No thought" methods, "the practitioner is fully alert, aware, and in control of their faculties but does not experience any unwanted thought activity."[38] This is in contrast to the common meditative approaches of being detached from, and non-judgmental of, thoughts, but not of aiming for thoughts to cease.[39] In the meditation practice of the Sahaja yoga spiritual movement, the focus is on thoughts ceasing.[40] Clear light yoga also aims at a state of no mental content, as does the no thought (wu nian) state taught by Huineng,[41] and the teaching of Yaoshan Weiyan.

One proposal is that transcendental meditation and possibly other techniques be grouped as an "automatic self-transcending" set of techniques.[42] Other typologies include dividing meditation into concentrative, generative, receptive and reflective practices.[43]

Frequency

The Transcendental Meditation technique recommends practice of 20 minutes twice per day.[44] Some techniques suggest less time,[33] especially when starting meditation,[45] and Richard Davidson has quoted research saying benefits can be achieved with a practice of only 8 minutes per day.[46] Some meditators practice for much longer,[47][48] particularly when on a course or retreat.[49] Some meditators find practice best in the hours before dawn.[50]

Posture

Young children practicing meditation in a Peruvian school

Asanas and positions such as the full-lotus, half-lotus, Burmese, Seiza, and kneeling positions are popular in Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism,[51] although other postures such as sitting, supine (lying), and standing are also used. Meditation is also sometimes done while walking, known as kinhin, while doing a simple task mindfully, known as samu or while lying down known as savasana.[52][53]

Use of prayer beads

Some religions have traditions of using prayer beads as tools in devotional meditation.[54][55][56] Most prayer beads and Christian rosaries consist of pearls or beads linked together by a thread.[54][55] The Roman Catholic rosary is a string of beads containing five sets with ten small beads. The Hindu japa mala has 108 beads (the figure 108 in itself having spiritual significance, as well as those used in Jainism and Buddhist prayer beads.[57] Each bead is counted once as a person recites a mantra until the person has gone all the way around the mala.[57] The Muslim misbaha has 99 beads.

Striking the meditator

The Buddhist literature has many stories of Enlightenment being attained through disciples being struck by their masters. According to T. Griffith Foulk, the encouragement stick was an integral part of the Zen practice:

Using a narrative

Richard Davidson has expressed the view that having a narrative can help maintenance of daily practice.[46] For instance he himself prostrates to the teachings, and meditates "not primarily for my benefit, but for the benefit of others".[46]

Religious and spiritual meditation

Indian religions

Hinduism

There are many schools and styles of meditation within Hinduism.[59] In pre-modern and traditional Hinduism, Yoga and Dhyana are practised to realize union of one's eternal self or soul, one's ātman. In Advaita Vedanta this is equated with the omnipresent and non-dual Brahman. In the dualistic Yoga school and Samkhya, the Self is called Purusha, a pure consciousness separate from matter. Depending on the tradition, the liberative event is named moksha, vimukti or kaivalya.

The earliest clear references to meditation in Hindu literature are in the middle Upanishads and the Mahabharata (including the Bhagavad Gita).[60][61] According to Gavin Flood, the earlier Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is describing meditation when it states that "having become calm and concentrated, one perceives the self (ātman) within oneself".[59]

One of the most influential texts of classical Hindu Yoga is Patañjali's Yoga sutras (c. 400 CE), a text associated with Yoga and Samkhya, which outlines eight limbs leading to kaivalya ("aloneness"). These are ethical discipline (yamas), rules (niyamas), physical postures (āsanas), breath control (prāṇāyama), withdrawal from the senses (pratyāhāra), one-pointedness of mind (dhāraṇā), meditation (dhyāna), and finally samādhi.

Later developments in Hindu meditation include the compilation of Hatha Yoga (forceful yoga) compendiums like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the development of Bhakti yoga as a major form of meditation and Tantra. Another important Hindu yoga text is the Yoga Yajnavalkya, which makes use of Hatha Yoga and Vedanta Philosophy.

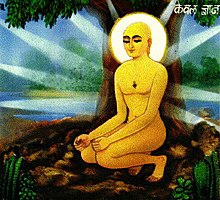

Jainism

Jain meditation and spiritual practices system were referred to as salvation-path. It has three parts called the Ratnatraya "Three Jewels": right perception and faith, right knowledge and right conduct.[62] Meditation in Jainism aims at realizing the self, attaining salvation, and taking the soul to complete freedom.[63] It aims to reach and to remain in the pure state of soul which is believed to be pure consciousness, beyond any attachment or aversion. The practitioner strives to be just a knower-seer (Gyata-Drashta). Jain meditation can be broadly categorized to Dharmya Dhyana and Shukla Dhyana.[clarification needed]

Jainism uses meditation techniques such as pindāstha-dhyāna, padāstha-dhyāna, rūpāstha-dhyāna, rūpātita-dhyāna, and savīrya-dhyāna. In padāstha dhyāna one focuses on a mantra.[64] A mantra could be either a combination of core letters or words on deity or themes. There is a rich tradition of Mantra in Jainism. All Jain followers irrespective of their sect, whether Digambara or Svetambara, practice mantra. Mantra chanting is an important part of daily lives of Jain monks and followers. Mantra chanting can be done either loudly or silently in mind.[65]

Contemplation is a very old and important meditation technique. The practitioner meditates deeply on subtle facts. In agnya vichāya, one contemplates on seven facts – life and non-life, the inflow, bondage, stoppage and removal of karmas, and the final accomplishment of liberation. In apaya vichāya, one contemplates on the incorrect insights one indulges, which eventually develops right insight. In vipaka vichāya, one reflects on the eight causes or basic types of karma. In sansathan vichāya, one thinks about the vastness of the universe and the loneliness of the soul.[64]

Buddhism

Bodhidharma practicing zazen

Buddhist meditation refers to the meditative practices associated with the religion and philosophy of Buddhism. Core meditation techniques have been preserved in ancient Buddhist texts and have proliferated and diversified through teacher-student transmissions. Buddhists pursue meditation as part of the path toward awakening and nirvana.[note 9] The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā,[note 10] jhāna/dhyāna,[note 11] and vipassana.

Buddhist meditation techniques have become popular in the wider world, with many non-Buddhists taking them up. There is considerable homogeneity across meditative practices – such as breath meditation and various recollections (anussati) – across Buddhist schools, as well as significant diversity. In the Theravāda tradition, there are over fifty methods for developing mindfulness and forty for developing concentration, while in the Tibetan tradition there are thousands of visualization meditations.[note 12] Most classical and contemporary Buddhist meditation guides are school-specific.[note 13]

According to the Theravada and Sarvastivada commentatorial traditions, and the Tibetan tradition,[66] the Buddha identified two paramount mental qualities that arise from wholesome meditative practice:

- "serenity" or "tranquility" (Pali: samatha) which steadies, composes, unifies and concentrates the mind;

- "insight" (Pali: vipassana) which enables one to see, explore and discern "formations" (conditioned phenomena based on the five aggregates).[67]

Through the meditative development of serenity, one is able to weaken the obscuring hindrances and bring the mind to a collected, pliant and still state (samadhi). This quality of mind then supports the development of insight and wisdom (Prajñā) which is the quality of mind that can "clearly see" (vi-passana) the nature of phenomena. What exactly is to be seen varies within the Buddhist traditions.[66] In Theravada, all phenomena are to be seen as impermanent, suffering, not-self and empty. When this happens, one develops dispassion (viraga) for all phenomena, including all negative qualities and hindrances and lets them go. It is through the release of the hindrances and ending of craving through the meditative development of insight that one gains liberation.[68]

In the modern era, Buddhist meditation saw increasing popularity due to the influence of Buddhist modernism on Asian Buddhism, and western lay interest in Zen and the Vipassana movement. The spread of Buddhist meditation to the Western world paralleled the spread of Buddhism in the West. The modernized concept of mindfulness (based on the Buddhist term sati) and related meditative practices have in turn led to mindfulness based therapies.[citation needed]

Comments

Post a Comment